The Mirror of Antiquity

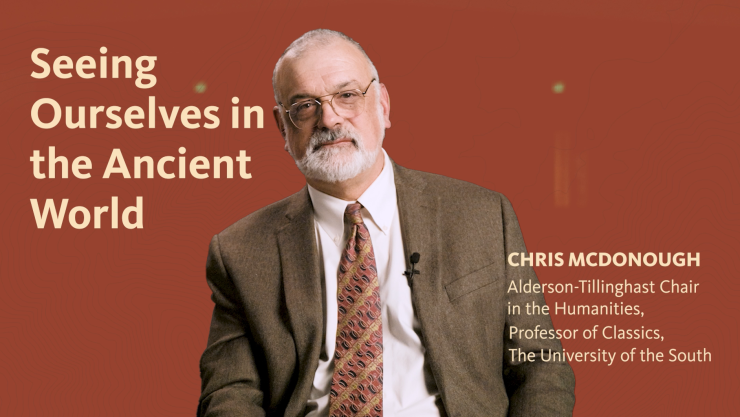

On a sun-dappled summer afternoon in the English countryside, Sewanee Classics Professor Chris McDonough stood with a group of students at Hadrian's Wall. A 73-mile long structure in the north of England, it had, for 300 years following its construction in A.D. 122, once stood as the northwest frontier of the Roman Empire. In that bucolic setting, with its rolling hills and nearby grazing sheep, one of the students turned to McDonough and said, “As I stand here, I feel like all the fairy tales and all the stories and all the myths that I've ever been told were actually true.”

For McDonough, it was the perfect encapsulation of both the ancient world’s endurance and how its very longevity is what keeps drawing us back to consider it. “That’s what I love,” he says. “You feel this way when you hold an old book. Who else held this book and read these words? What was their life like? These [ancient] things ... they persist.”

For McDonough, it was the perfect encapsulation of both the ancient world’s endurance and how its very longevity is what keeps drawing us back to consider it. “That’s what I love,” he says. “You feel this way when you hold an old book. Who else held this book and read these words? What was their life like? These [ancient] things ... they persist.”

So extensive was the Roman Empire’s reach through both space and time that one hardly needs to travel all the way to England to be able to look into antiquity. Take Washington, D.C., for instance, where classical influence is on display in the plethora of white, columned buildings like the U.S. Capitol (which emulates Roman temples) and the Smithsonian (inspired by the Parthenon). “They want it to look like an important place, so they build these classical buildings,” says McDonough. “When Nashville celebrates Tennessee’s centennial, what do they build? They build themselves a Parthenon.”

Closer to Sewanee, just down the Mountain in Cowan, McDonough notes the auspicious presence of a 1930s monument in recognition of the Cowan Cement Company’s industrial safety record. Pictured on its facade are two classical figures: a bare-chested male figure holding a gear and the Greek goddess Athena holding an ancient lamp. Engraved below them are the words, “Safety Follows Wisdom.”

Closer to Sewanee, just down the Mountain in Cowan, McDonough notes the auspicious presence of a 1930s monument in recognition of the Cowan Cement Company’s industrial safety record. Pictured on its facade are two classical figures: a bare-chested male figure holding a gear and the Greek goddess Athena holding an ancient lamp. Engraved below them are the words, “Safety Follows Wisdom.”

“I find this fascinating,” says McDonough. “It’s this elevating kind of thing. We’re reaching up to something that’s ideal and classical and platonic, something beautiful and larger than life.”

That aspirational dynamic of locating present-day concerns and triumphs within a context of ancient empiric ideals exemplifies for McDonough the concept of the mirror of antiquity. Whether through reading texts that have survived millennia or watching contemporary gladiator films, when we turn our gaze to the ancient world, we can’t help but see ourselves and our contemporary concerns reflected—or refracted—in it.

“That, to my mind, is really when classical reception becomes interesting,” says McDonough. “When the living voices of students and teachers are talking together about what these stories mean, that’s when the classics are most alive and that’s what classical reception is all about.”

For McDonough, it was the perfect encapsulation of both the ancient world’s endurance and how its very longevity is what keeps drawing us back to consider it. “That’s what I love,” he says. “You feel this way when you hold an old book. Who else held this book and read these words? What was their life like? These [ancient] things ... they persist.”

For McDonough, it was the perfect encapsulation of both the ancient world’s endurance and how its very longevity is what keeps drawing us back to consider it. “That’s what I love,” he says. “You feel this way when you hold an old book. Who else held this book and read these words? What was their life like? These [ancient] things ... they persist.”

Closer to Sewanee, just down the Mountain in Cowan, McDonough notes the auspicious presence of a 1930s monument in recognition of the Cowan Cement Company’s industrial safety record. Pictured on its facade are two classical figures: a bare-chested male figure holding a gear and the Greek goddess Athena holding an ancient lamp. Engraved below them are the words, “Safety Follows Wisdom.”

Closer to Sewanee, just down the Mountain in Cowan, McDonough notes the auspicious presence of a 1930s monument in recognition of the Cowan Cement Company’s industrial safety record. Pictured on its facade are two classical figures: a bare-chested male figure holding a gear and the Greek goddess Athena holding an ancient lamp. Engraved below them are the words, “Safety Follows Wisdom.”