Lessons from the Apocalypse

Monsters. Zombies. Cataclysm. For Britt Threatt, assistant professor of English, these hallmarks of speculative genre fiction are more grounded in reality than they might at first appear.

Long seen in academic circles as the less artistically serious cousin of literary fiction, genre fiction encapsulates a broad swath of writing focused primarily on the development of plot over prose. Driven by conventions—like the meet-cute in a rom-com, or the monster to be slayed in a fantasy—these novels, says Threatt, play with the familiar and the extraordinary, allowing us to approach the very real challenges of our world through the lens of metaphor.

Broadly speaking, speculative fiction stories follow a similar three-act structure. In the first act, we’re introduced to the status quo world, meeting our hero or heroine and seeing the problems they’re facing. Then, we’ll see our hero transported to another world—the “upside down” world—by, say, passing through the wardrobe into Narnia or taking the train to Hogwarts, where the hero now has to do things differently. In this new world, the hero is forced to change, and perhaps they meet a mentor or new friends who will help them in the pursuit of their new objective (e.g., slaying a dragon).

In act three, after the goal has been met and the (real or metaphorical) dragon slayed, the hero returns back home to the status quo world. But they return to that world as a changed person because of what they’ve seen and experienced, and they can revisit their earlier problems with a new set of skills and greater ability to overcome them.

For Threatt, the hero’s journey back to the familiar world of act one, only now with new questions and strategies for survival, mirrors the journey that readers of speculative fiction take. Readers leave their status quo world via the pages of a novel, journey with its characters as they encounter and overcome hardship, and resume “real life” at the novel’s end changed by what they’ve read.

“What I like about speculative fiction is that it invites, provokes, and necessitates questions. It offers us a different lens to be able to see difficult things from new perspectives,” says Threatt. “For instance, it’s easier to understand bias when you look at how a zombie is treated versus how a human is treated. And then you can ask: Who are the zombies in our world, and how are they treated?”

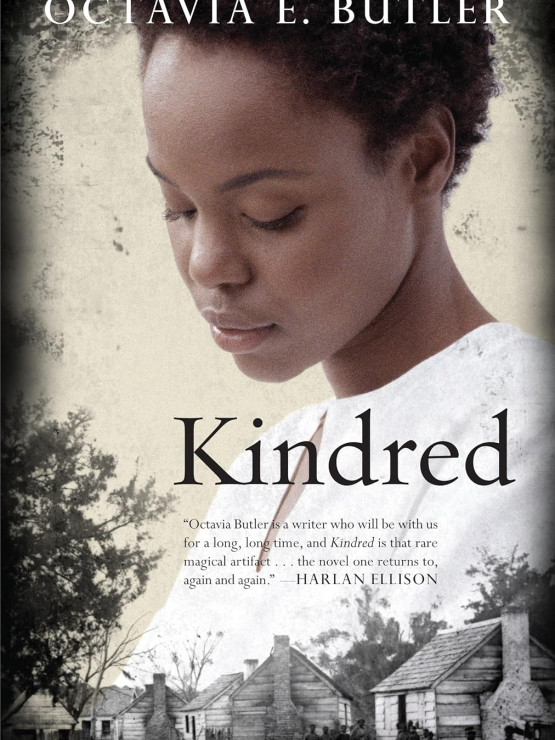

That these fantastic elements shed new light on our all-too-real troubles is key to how Threatt sees genre fiction as grounding, and not, at its core, escapist. However exaggerated or outlandish their premises, these novels touch on concerns and anxieties that are present in our immediate reality. Take, for example, Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower. Published in 1993 but taking place in 2024, the novel envisioned a society undone by the ravaging effects of climate change. The novel’s setting? A fictionalized Southern California town much like Altadena, the site of devastating wildfires earlier this year.

“We're living in a time where [predicting] how likely something is to happen is a fool's question,” says Threatt. “Everything is happening that we never thought would happen. The question is, what are the goals, what are the obstacles, and how are we going to answer that?”

The solution, says Threatt, is to read more genre fiction.

“If you’re feeling like we are in a brave new scary world where unexpected things are happening, pick up a fiction book. Look for one in which the status quo world is a little bit familiar,” says Threatt. “You will see a character do what appears to be escape. But you will also see the ways in which, in this different world into which they escaped, they encounter the same things and they learn how to deal with them precisely because those things look different. And you, gentle reader, will also see a way that you can be in the world.”