English Courses

English 101 will set you to work planning, writing, and revising essays of various lengths, practicing a handful of essential skills that make for clear and persuasive writing. The content of each courses differs widely, from medieval poetry to contemporary drama, from African-American memoir to speculative fiction.

In Representative Masterpieces, we explore the epic tradition’s origins in classical antiquity, moving from Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey through Vergil’s Aeneid. Beginning with the first and greatest of all war stories, the Greek army’s decade-long siege at the gates of Troy, we will trace reverberations of violence in the family life of the cunning Greek warrior Odysseus and the divinely-ordained mission of the Trojan captain Aeneas, who gathers his city’s survivors to establish a new home in Italy. Central concerns include the nature of war, peace, and honor, morality on earth and among the gods, the role of gender, and the genesis of political power.

This course examines not merely texts about University women (those who work there, study there, or subsidize the place), but also the historical place of women in higher education, how its institutions have been involved in debates about political representation, gender and sexual identities, labor activism, and discourses of care and vocation. This will take us deep into conversations about class privilege, white feminism, campus activism, neoliberalism, and academic precarity. How have people attached to the idea of the University, and how have those attachments influenced the freedom of women to do intellectual work? How do changing notions of “safe space” and free speech bear on women’s experience of living and working in academe?

Students in this class will read some interesting works about teaching and learning in a range of genres: essays by Virginia Woolf, bell hooks, Audre Lorde, Sara Ahmed, mystery novels by Dorothy Sayers and Amanda Cross, plays by Adrienne Kennedy, Margaret Edson and Ameera Conrad’s activist coalition of students at the University of Cape Town, campus novels by Julie Schumacher and Zadie Smith, and a few popular films and television episodes. They will come away with a more sophisticated sense of how a campus works as well as where and how power is concentrated in higher ed spaces. The pace of reading will accommodate the course’s writing-intensive attribute, and students will also have some choice in the kinds of writing they want to do.

This course is an introduction to literary history via Mary Shelley’s perennially fascinating novel. In addition to reading the novel itself through a variety of critical lenses, we will explore its source material in Greek mythology, the Faust legend, Milton, Romantic poetry, and eighteenth-century science. We will also examine the afterlives of the story through various films and novels of our own time.

How do you narrate a life? How do gender, race, class, and place inform experiences of selfhood? What's the difference between memoir and autobiography, and how do we parse and examine our varied understandings of "truth" when it comes to articulating stories of identity and history? Our class will explore these questions through the works of authors such as Audre Lorde, Alison Bechdel, and Harry Crews--among others. Students will write several short memoir pieces as well as analytical essays.

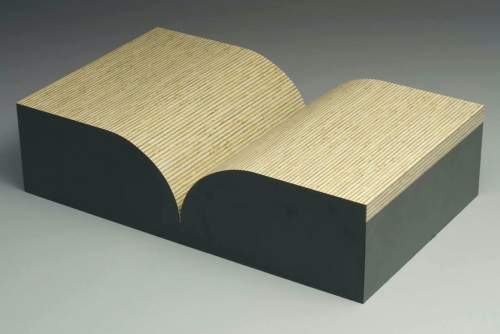

Organized around a genre—the novel—rather than a single historical period or geographical context, this course reintroduces students to a familiar form whose aesthetic and conceptual parameters we too often take for granted. After all, what is a novel? Is a novel simply any long fictional work of prose? Or does the term refer to a specific literary-historical tradition, a repertoire of stylistic techniques, a structure of thought, an affinity for certain kinds of content? How do novels differ from one another and what core characteristics do they all embody? Are novels fundamentally realist or speculative? What insights about psychology and social life do novels make possible? How do novels relate to the cultures in which they were written, and what makes them legible outside those contexts? Can you have a novel without characters? Without a plot? How do novels intersect with other genres, such as epic, fairytale, drama, non-fiction, or autobiography? What critical methods are available to us when we study novels? What can novels do that other kinds of writing and thinking can’t?

Students will read novels from a variety of traditions alongside material drawn from the critical fields of novel theory and narratology. Possible texts to be determined, but may include novels by Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, Thomas Hardy, Vladimir Nabokov, Toni Morrison, and/or Salman Rushdie.

This course will examine the work of Geoffrey Chaucer, a major writer of the 14th century. His poetry stands at the head of a long tradition, and has consistently been admired and imitated since his death. In fact, Chaucer has, for several centuries, been known as the “father of English poetry” (John Dryden called him this in 1700). Indeed, when people think, “English literature” they often think, “Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton.”

However, this doesn’t speak to how weird Chaucer’s writing is. He wrote profound, erotic, and downright filthy poems, and wrote them without necessarily expecting to spawn a literary tradition. In this course, we will learn about Chaucer’s literary and philosophical background, learn his language (Middle English), and examine both critical and theoretical approaches to research on Chaucer, with a focus on gender (this course also counts towards Women’s and Gender Studies). The course, which is Writing Intensive in the Major, will provide students with training in writing a research paper. And in doing all that, we will discover anew one of England’s weirdest writers.

A study of women’s literature before 1800, this course examines how feminine voices were presented and heard in their historical contexts. Readings for the class are drawn from the Middle Ages through the seventeenth century and ask students to think through the conditions of feminine authorship and identity in the pre-modern period.

Our focus will be on The Lais of Marie de France, Christine de Pizan's The Book of the City of Ladies, Marie de Gournay's On the Equality of Women And Men, Elizabeth Cary’s Tragedy of Miriam, Anne Locke (first English author to publish a sonnet sequence), Isabella Whitney (first Englishwoman to publish original secular poetry under her own name), Aemelia Lanyer (first woman to be a professional poet), Aphra Benn’s Oroonoko and The Rover, Mary Astell’s Serious Proposal, and The Blazing World of Margaret Cavendish (first woman to visit the all-male Royal Society).

This class will consider Shakespeare’s plays up through the year 1600 CE. This corpus is anchored by Shakespeare’s two great history-cycles and some of his best-loved tragedies and comedies. It also, however, includes plays that are notoriously difficult to stage and come to terms with. Our investigation will focus on the idea of conclusions -- asking just where these texts leave us after the curtain falls. We will look at plays that are remarkably similar, almost as if they were rewritten versions of each other but composed with different ends in mind. We will consider plays that exist in sequence, continuing a single storyline from one text into another. And we will grapple with plays that lean on villainized (or lauded) tropes that we do not recognize today, asking what their current lives (and ends) should be both in performance and in the classroom.

English 365 covers the period from the Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in 1660 through the late eighteenth century. In addition to considering purpose of satire—including whether or not satire can survive in an age of true absurdity—we’ll devote significant attention to prose fiction and non-fiction. Works considered include the satires of John Dryden, Jonathan Swift, and Alexander Pope; Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko, or the Royal Slave; Mary Wortley Montague’s Turkish Embassy Letters; The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African; the popular essays of Joseph Addison, Richard Steele, and Samuel Johnson; and Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe.

At right, John Wilmot, the 2nd Earl of Rochester, bestows the laurel wreath of poetic achievement upon a court friend showing him some original verse.

Victorian literature is famously preoccupied with the past: memory and personal experience, national history, nostalgia, and repressed trauma. At the same time, Victorian culture encouraged a robust faith in various visions of progress: the possibility of self-determination, advances in science and technology, and the growth of England as a nation. In this survey of Victorian poetry and non-fiction prose, we will read works of literary and intellectual significance by writers whose preoccupations ranged widely—from romantic desire to evolutionary science, from religious belief to the rise of capitalism. Yet they all grappled with the relationship between art, individuals, and the ever-changing society they inhabited. As we put these fascinating works in dialogue with one another, we will pay special attention to their representations of individual and collective pasts, presents, and futures.

Texts include poetry by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Robert Browning,

Matthew Arnold, Algernon Swinburne, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Christina Rossetti, Gerard

Manley Hopkins, and Thomas Hardy, as well as essays and non-fiction prose by Thomas

Carlyle, John Stuart Mill, Friedrich Engels, Charles Darwin, Matthew Arnold, John Ruskin,

William Morris, and Oscar Wilde.

This course, the first half of the two-semester survey of American literature before the twentieth century, begins with the earliest writings in English by European explorers and colonizers and follows the slow emergence of distinctive political, moral and literary traditions that were recognizably American. It thus features, along with poetry and fiction, a good deal of nonfiction writing in the form of essays, memoirs, and sermons. The course culminates with the period usually called “the American Renaissance,” a thirty-year span just before the Civil War in which internationally important works were created by such writers as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Edgar Allan Poe, Frederick Douglass, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, and Walt Whitman.

“In the four quarters of the globe,” sneered the English critic Sidney Smith in 1820, “who reads an American book?” This course introduces the U.S. writers who answered Smith’s challenge, such as Hannah Webster Foster, James Fenimore Cooper, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Henry James, Charles W. Chesnutt, Willa Cather, and Theodore Dreiser. They invented a distinctively American novel and in the process produced masterpieces that are still recognized in all four quarters of the globe.

This course introduces students to modern Irish and Northern Irish poetry, fiction, and drama, beginning with Yeats and the last phase of the Celtic Revival and reaching up through the short-lived Celtic Tiger of the Twenty-First Century. These texts are concerned with borders and bequests of all kinds, but class discussions focus primarily on literary responses to high modernism, cultural nationalism and the Irish language, sectarian violence, and the role of the Catholic Church. The survey explores these historical and cultural contexts, observes the different kinds of critical attention these genres demand, and emphasizes the practice of close reading.

In this course we will get into perceptions of truth by looking for it in speculation. Gossip, secrets, hearsay, innuendo. What can these things tell us about truths not allowed to circulate unchallenged in the mainstream narrative? Through reading narratives of those usually overlooked (enslaved persons, domestic workers, etc.), we will look at moments in American history from the bottom-up. In doing so, we will discover greater insight and great contradictions to the prevailing history.

While national or regional designations—British, American, or Southern, for example—often shape the fields of English literary study, this course is organized around literature that emerges from societies that have been affected by British colonialism. The course introduces the challenges of defining and reading such varied literatures while pursuing the central questions, concepts, and debates in postcolonial Anglophone literary study through reading poetry, drama, essays, and fiction from the Caribbean, Africa, and South Asia. This includes works from Derek Walcott, Jamaica Kincaid, Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Tsitsi Dangarembga, Nadine Gordimer, J. M. Coetzee, Salman Rushdie, Arundhati Roy, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. The course open with a consideration of the possibilities and perils of writing in English: how can these authors adapt the English language and its literary expressions to new rhythms of speech, new forms of expression, and new modes of thinking? How do they acknowledge the impositions of British colonialism while representing the diversity of their societies and cultures? To answer these questions, we will explore how these authors view the writing of literature as a world-making activity that theorizes our relationship to history, nature, violence, forgiveness, otherness, and community. Our class conversations will attend to how authors, often risking arrest or exile, turn to literature to develop their ethical, social, and political commitments and to intervene in local and global conversations about gender, race, and national identity. We will take up these considerations while viewing global Anglophone literature as a powerful site for making visible the histories, debates, and forces that continue to shape the contemporary world.

Additional Attributes: International and Global Studies (Global Culture and Society); Women and Gender Studies.

An advanced research methods and composition course required for students pursuing honors in the department. The class will introduce students to the process of conducting independent research in the field of English and will provide experience with the most common research tools and methods used by scholars of literary analysis. We will discuss argumentative structures, disciplinary conventions, and work together in a collegial and cooperative environment that gives students experience with scholarly collaboration. Class sessions will be devoted to giving students in-class writing time, offering peer critiques, reflecting on the nature of scholarly writing, and working through exercises to develop and discover students’ individual voices and analytic priorities. In addition, students will work closely with their thesis advisor throughout the term as part of the course requirements, meeting with their advisor regularly outside of class for individual guidance and feedback about their project. By the end of the semester, students will have produced an initial rough draft of their thesis project that will then be revised in a more leisurely manner, under the supervision of their thesis advisor, during the following term.

Admission to the class is granted by the department. To be selected, students must submit an abstract of their intended project over the summer and the department will approve the abstracts they believe will produce successful honors theses.

Creative Writing Courses

Discussions will center on students' poems. Selected readings are assigned to focus on technical problems of craftsmanship and style.

How do we tell stories that matter? How do we make our voice heard in a way that connects us to the larger world?

If you’re interested in storytelling, the Beginning Fiction Workshop provides you with the opportunity to develop your skills, study unique and diverse stories from contemporary literature, and share and discuss creative work amongst a group of students in a welcoming space. The primary goal of the course is to help each writer find their own particular voice while utilizing distinct elements of craft. The beginning workshop allows for students to generate multiple stories over the course of the semester, and over the course of the semester we will develop a common language so we can discuss these stories with sensitivity, specificity, and generosity.

If you’re dreaming up ways to tell new stories, the Beginning Fiction Workshop provides a welcoming space to explore techniques to hone your skills as a writer of fiction. You will read a diverse array of stories while we create a common language to aid us in discussion of the stories we study and create. You will write through generative exercises and build toward your own stories. Each writer will uncover their writing voice while becoming a part of the larger writing community. Together, we will become studied observers and generous participants in the writing and reading of fiction.

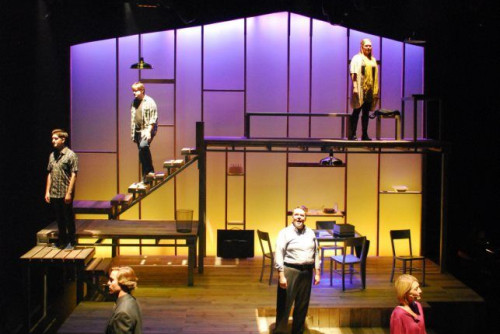

Are you a fan of The Flight Attendant or House of Cards? Do you love Raya and the Last Dragon, Encanto, or Turning Red? What do they all have in common? They were all written by playwrights.

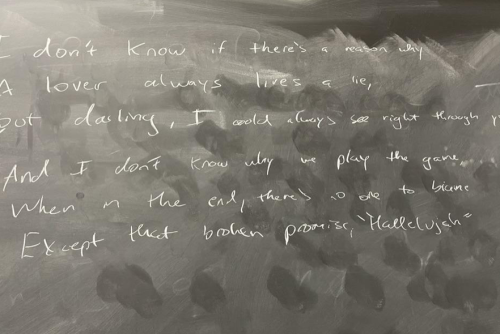

Whether you are a fiction writer interested in improving your dialogue, a poet who wants to explore narrative, a theatre geek who wants to see their work come to life, or someone simply interested in trying something new, Beginning Playwriting Workshop is an excellent opportunity to explore dramatic writing in a safe and supportive environment. Emphasis is placed on promoting growth as a writer. A variety of foundational texts are read in order to develop an understanding of basic dramatic structure. Each play is chosen to address a corresponding skill, such as dramatic tension, subtext, dialogue, exposition, or character. Weekly writing exercises are assigned to work in concert with the plays we read. By reading plays and dissecting the form and content, students have an opportunity to develop their analytic skills, which can then be applied to their own work. In addition to short writing exercises, students will also complete either two 10-minute plays or a one-act play.

Why study and write the novella? The novella, unlike the novel, is wieldy enough to be imagined, written, and workshopped over the course of a semester. Similarly, its form, and literary merit can be examined in some depth over 15 weeks. Shorter than a novel—between 18,000 and 25,000 words—but longer than a traditional short story—really, the middle child of the word count world—the novella, or as some might cheekily call it “the short novel,” is the perfect form to practice writing long form fiction—be honest, you’ve been working on a novel since you were 12 and you’re convinced that this particular “novel” needs another form to fit into, one that allows you to actually finally finish a complete draft!—so this seminar will be devoted to making that happen. In this class we will examine the three-act story structure, elements that go into crafting an outline, and endings. We will give careful consideration to cultivating the following aspects of fiction in our own writing: how to develop major and minor characters, how to utilize different point-of-view strategies, how to develop acute and chronic tension and how to maintain these two types of tension to keep a reader engaged in the story, how to establish and utilize the setting a story takes place in, how to sustain voice, how to deploy subtext and stage desire in extended scenes etc. We will read, read, read because as R. O. Kwon said, reading is as much, if not, more important than writing! We will feet-to-the-fire (you gotta take the class to find out what this is) every week and eat sadness pizza as we make certain that none of us share the fate of the deer featured in the photograph!

In the advanced workshop, students focus on their capstone project, sharing that work with peers in a workshop setting. The course requires students to work with the professor to develop specific reading lists with the goal of shaping their own capstone project. The primary focus of the workshop is the creation and critique of their own work and the work of their peers. Open only to students pursuing programs in creative writing.

In the advanced workshop, students focus on their capstone project, sharing that work with peers in a workshop setting. The course requires students to work with the professor to develop specific reading lists with the goal of shaping their own capstone project. The primary focus of the workshop is the creation and critique of their own work and the work of their peers. Open only to students pursuing programs in creative writing.

In the advanced workshop, students focus on their capstone project, sharing that work with peers in a workshop setting. The course requires students to work with the professor to develop specific reading lists with the goal of shaping their own capstone project. The primary focus of the workshop is the creation and critique of their own work and the work of their peers. Open only to students pursuing programs in creative writing.