Finding an Exciting Sound

There are few moments more laden with anticipation than the sudden gasp of silence in a concert hall just before an orchestra starts to play. Back to the audience, the conductor lifts his hands, the buzz of the crowd fades, and 100 musicians’ eyes look in the same direction as they await their leader’s opening move. That first gesture, be it a sharp punch or a soft wave, is the first step in a sort of musical chain reaction wherein the conductor’s energy passes to the first section of musicians and builds as others join the swell.

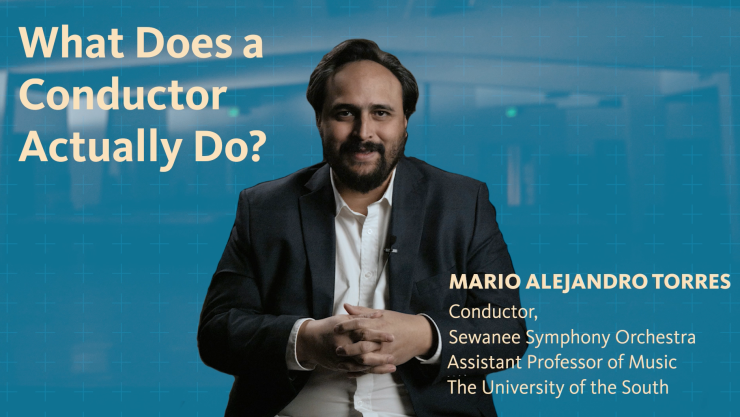

“You take a few seconds to be calm and concentrate on the true character of the introduction,” says Mario Alejandro Torres, assistant professor of music and conductor of the Sewanee Symphony Orchestra. “And then you unfold in such a way that the gesture is coming not from your hand, but from your core—from the fire inside of you.”

For Torres, that sharing of musical energy is the true essence of what a conductor does. “Many people think of a conductor as being a timekeeper, but that’s just part of what making music is about,” says Torres. A good orchestra, he notes, can keep time on their own without need of a conductor’s gestures. What conductors bring to the table is the capacity to knit together their ideas about the music—and the diverse perspectives of the sometimes hundred-plus musicians in the orchestra—into one united, emotionally resonant whole.

One reason why conductors bear this responsibility is the underlying physics of how sound waves travel within a performance space. Each instrument, from the strings to the woodwinds and the brass to the percussion, produces sound with its own specific intensity. Quieter instruments, like the strings, require more musicians and placement at the front of the grouping to ensure an adequate presence within the sound. Louder instruments, like the brass or drums, are fewer in number and placed farther back.

Where a musician sits onstage—and who sits right next to or behind them—has major implications for what they can hear. “If you sit next to a trumpet,” says Torres, “you can barely hear the woodwinds, and you cannot hear at all what the string instruments are doing.” But from in front of the entire orchestra, the conductor can hear and connect to every section and, via gesture, facilitate connections between instrumentalists even when they cannot hear one another.

That trusting connection is, in Torres’ view, what music is all about—not just between the musicians and their conductor, but also between the orchestra and its audience. “One of the calls that we have as musicians is to connect with our communities,” says Torres. The presence and energy of the audience is as crucial to the onstage musical alchemy as that of the conductor. Seeing friends and family in the crowd makes it more personal and joyful for the musicians. And in the ephemeral environs of a live performance, that sense of joy translates into a unique, never-to-be-heard-again interpretation of the music.

“Enjoy the artistic life of your community. Go to concerts, go to art exhibitions, go and explore art,” says Torres. “Because life is getting busier and busier and we need to take a step back, breathe, and connect with ourselves and our humanity. And there’s no better way to do that than experiencing art.”