What Nature's Song Tells Us

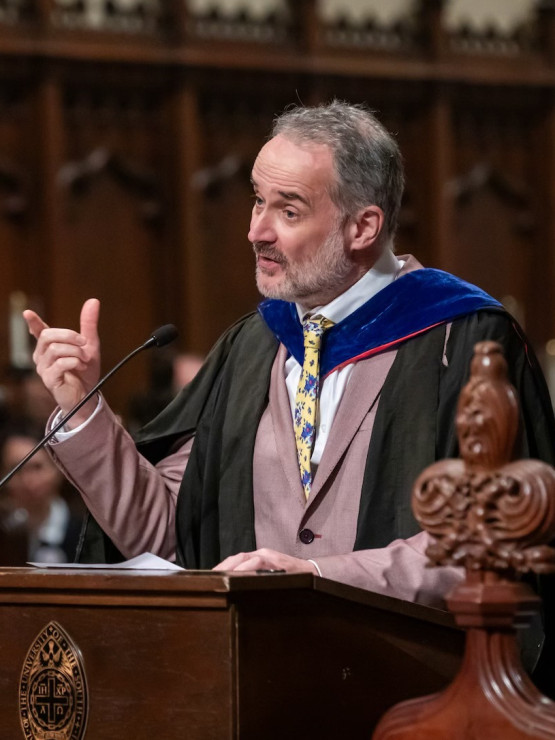

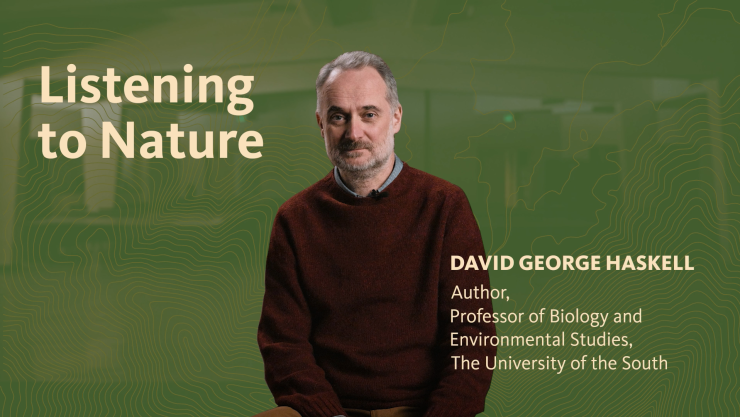

What does “nothing” sound like? For many, the first sound that comes to mind is that of crickets—like in those excruciating moments after a comedian tells a joke that fails to land. But for David Haskell, William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Biology and Environmental Studies, the sound of crickets calls to mind something much more epic in scope than just the mere absence of other sounds.

“There’s an enormous amount to be learned from just listening to the very ordinary sounds of insects,” says Haskell. What we hear as buzzing or chirping is, in Haskell’s words, “an extraordinary blossoming of sonic energy.” Energy is beamed from the sun to Earth, where it is converted by plant life into the energy needed to flower and grow. Insects feed on tree sap and leaves, consuming that energy and then using it to fuel its own activity and sound production. Thus, when we hear the sounds of insects, says Haskell, “We’re listening to sunlight refracted through trees and through insect life into the conscious human experience of hearing.”

Our very hearing, Haskell notes, is the result of millennia of evolutionary and adaptive processes. When our ancestors first emerged from the sea, their above-water hearing was extremely poor. Attuned to low-frequency sounds of the underwater world, they initially lacked the ability to perceive higher frequencies in the air. But with the insects calling—“a protein snack that was advertising its presence through song,” says Haskell—an intense natural selection ensued, prompting mammals’ predecessors to develop eardrums and other tools to hear those higher ranges and more effectively feed themselves.

Our very hearing, Haskell notes, is the result of millennia of evolutionary and adaptive processes. When our ancestors first emerged from the sea, their above-water hearing was extremely poor. Attuned to low-frequency sounds of the underwater world, they initially lacked the ability to perceive higher frequencies in the air. But with the insects calling—“a protein snack that was advertising its presence through song,” says Haskell—an intense natural selection ensued, prompting mammals’ predecessors to develop eardrums and other tools to hear those higher ranges and more effectively feed themselves.

Not only how we hear, but what we hear can be similarly understood as the result of selection and optimization. “When we listen to birds, we often get carried away with a beautiful melody or are reminded of when we last heard that bird sing, and that’s it. We hear the bird, have a response, and move on,” says Haskell. “What I encourage my students to do is to listen to the story behind the sound.”

Birds of the forest, for example, have to contend with the reverberation of their songs’ sound waves bouncing off of every leaf and tree trunk and twig. To make sure they’re heard, these birds will sing slow, whistled songs. But birds of the open prairie don’t face those same constraints, permitting them to intone a more virtuosic song, full of trills and frequency sweeps. Coastal birds offer loud, piercing cries to be heard above the roar of waves.

The coincidence of sound to its environment is not limited to wildlife. Think, for instance, of how great choral music sounds in a massive, reverberant cathedral, of how violins and pianos match a 19th-century concert hall, or of the perfectly calibrated intimacy of Billie Eilish whispering directly to you through your earbuds. We can trace this concept back through history to the caves of what is now southern Germany, where some of the first human instruments—flutes made from the wing bones of birds or carved out of mammoth ivory—were unearthed. “Where does a flute sound really good?” asks Haskell. “In a cave, with lots of reverb.”

The coincidence of sound to its environment is not limited to wildlife. Think, for instance, of how great choral music sounds in a massive, reverberant cathedral, of how violins and pianos match a 19th-century concert hall, or of the perfectly calibrated intimacy of Billie Eilish whispering directly to you through your earbuds. We can trace this concept back through history to the caves of what is now southern Germany, where some of the first human instruments—flutes made from the wing bones of birds or carved out of mammoth ivory—were unearthed. “Where does a flute sound really good?” asks Haskell. “In a cave, with lots of reverb.”

Noting the inextricable ties between nature’s songs and human music, Haskell believes we can all benefit from taking the celebratory listening rituals that we’ve developed for things like concerts and applying them to our natural sonic environment. “When you step outside, instead of popping in your earbuds to listen to a podcast, listen to what’s around you. Be present in the space and treat what you hear as a unique composition that the world has produced just for you, that will never again reoccur as it is happening right now,” says Haskell. “In 50 or 100 years, when we’re dead and gone, will those sounds still be here? We don’t know. What we do know is that there will be people alive who need to hear our stories from now. And if we haven’t paid attention, what are we going to tell the future?”

Our very hearing, Haskell notes, is the result of millennia of evolutionary and adaptive processes. When our ancestors first emerged from the sea, their above-water hearing was extremely poor. Attuned to low-frequency sounds of the underwater world, they initially lacked the ability to perceive higher frequencies in the air. But with the insects calling—“a protein snack that was advertising its presence through song,” says Haskell—an intense natural selection ensued, prompting mammals’ predecessors to develop eardrums and other tools to hear those higher ranges and more effectively feed themselves.

Our very hearing, Haskell notes, is the result of millennia of evolutionary and adaptive processes. When our ancestors first emerged from the sea, their above-water hearing was extremely poor. Attuned to low-frequency sounds of the underwater world, they initially lacked the ability to perceive higher frequencies in the air. But with the insects calling—“a protein snack that was advertising its presence through song,” says Haskell—an intense natural selection ensued, prompting mammals’ predecessors to develop eardrums and other tools to hear those higher ranges and more effectively feed themselves. The coincidence of sound to its environment is not limited to wildlife. Think, for instance, of how great choral music sounds in a massive, reverberant cathedral, of how violins and pianos match a 19th-century concert hall, or of the perfectly calibrated intimacy of Billie Eilish whispering directly to you through your earbuds. We can trace this concept back through history to the caves of what is now southern Germany, where some of the first human instruments—flutes made from the wing bones of birds or carved out of mammoth ivory—were unearthed. “Where does a flute sound really good?” asks Haskell. “In a cave, with lots of reverb.”

The coincidence of sound to its environment is not limited to wildlife. Think, for instance, of how great choral music sounds in a massive, reverberant cathedral, of how violins and pianos match a 19th-century concert hall, or of the perfectly calibrated intimacy of Billie Eilish whispering directly to you through your earbuds. We can trace this concept back through history to the caves of what is now southern Germany, where some of the first human instruments—flutes made from the wing bones of birds or carved out of mammoth ivory—were unearthed. “Where does a flute sound really good?” asks Haskell. “In a cave, with lots of reverb.”