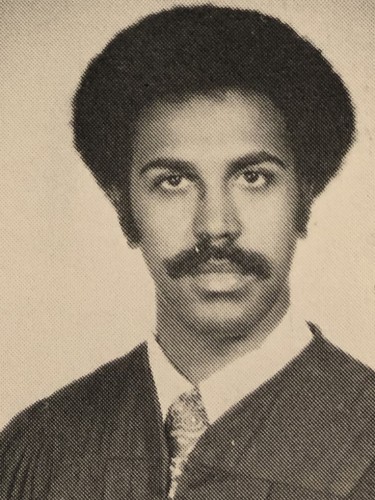

When Earl Shores, C’76, entered Sewanee through the actions of famed admission officer Betty Nick Chitty, he already had a degree in computer science and had already spent a few years in the Vietnam-era US Air Force. In the mid-70s, Sewanee had few Black students, and, according to a contemporaneous article in the Sewanee Purple, few opportunities for a rich social life. “A black student who comes to Sewanee is in limbo for four years,” observed James Floyd, C’77, in the November 12, 1976 Purple.

Nick Chitty, he already had a degree in computer science and had already spent a few years in the Vietnam-era US Air Force. In the mid-70s, Sewanee had few Black students, and, according to a contemporaneous article in the Sewanee Purple, few opportunities for a rich social life. “A black student who comes to Sewanee is in limbo for four years,” observed James Floyd, C’77, in the November 12, 1976 Purple.

As a veteran and a married student, by contrast, Shores had a social life that was rooted in the Sewanee community. His wife, Patricia Shores, was a nurse at Sewanee, and the couple lived with his mother and stepfather, Dora (Shores Turner Taylor) and Isaac Turner “Sewanee was getting the best and brightest at the time, and not many local Black students were attending,” says Shores. “I was a test student. I was given maximum help, I felt.”

Starting as a mathematics major, Shores tried philosophy and ended with a degree in religious studies. “My liberal arts education really served me well,” Shores observed. “If you go to work for a company, the company really has to teach you their method. The liberal arts might not prepare you for specific work, but it can prepare you to roll into almost any job. I learned I can talk to almost any level of person, from presidents to the homeless.” For decades, Shores used that ability to communicate in a public facing role with Continental Airlines and its successor United Airlines.

While Shores was not an air force pilot, he has had a lifetime fascination with flight, from making model airplanes as a boy to his work with Continental and United. He was working toward a pilot’s license when he was diagnosed with glaucoma. “I flew a Cessna to Sewanee once,” he says. “It’s an unforgiving airport.”

In part, Shores’ resilience must have also come from his childhood, growing up on one the largest black owned farms in Franklin County, where he lived with his parents and grandparents, Annie and Edd Burnett. “We were pretty self-sufficient,” remembers Shores. “We had a garden and grew chickens, cows, pigs, and wheat, which we ate and also sold. We grew corn for the animals and a little cotton.” Shores worked alongside his father in his early childhood, while his grandfather also worked for the railroad.

In the mid 1960s, life changed for Shores. Schools were integrated, and he finished high school at the majority-white Franklin County High School, where a family friend, Elna Murray, worked as a guidance counselor. And then, in 1967, as Shores was graduating, his father was killed by a drunk driver while traveling for work. Shores wanted to go to college in Florida, but he settled for study at Chattanooga State, alternating between working a term and going to school a term so that he could earn money for college. “During one of my terms working, I was drafted,” he says. That is when Shores joined the Air Force.

After Sewanee, the Shores Family moved to Elyria, Ohio, a suburb of Cleveland, where they have lived ever since. They joined a contingent of uncles and their families, who had moved there in the 1960s for work in industry.

Shores is thankful for a Sewanee education that enriched his life through a liberal arts education and prepared him to succeed in his chosen career. “No matter what I give, I can’t repay my education,” he says. “But whatever I give helps someone else.”