Fieldwork in Freshwater

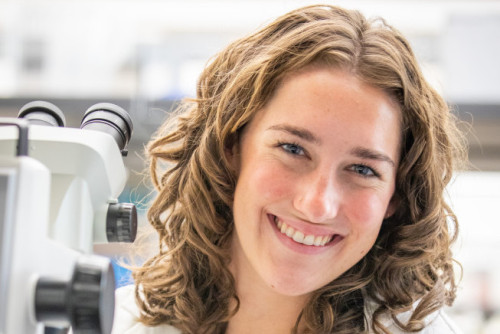

By Emma Steadman, C'26

It’s a warm summer morning at Beans Creek, and sunlight filters through the trees, dappling the narrow, winding waterway. Mary Elizabeth Jackson, C’26, and Bryce Martin, C’28, stand near the water, preparing to place a giant net in it. The net slices through the cool stream, settling against the rocky bottom as the two students brace it in place. Another pair of waders upstream disturbs the substrate, causing a swirl of silt and fish to charge forward.

The net comes alive almost immediately with bursts of orange, blue, silver, and brown glistening among the clear water. Caught in the net is a small, yellow catfish with bead-black eyes and long white whiskers known as the slender madtom—exactly what they’re looking for. With over 20 species of fish swimming through the creek’s narrow channels and undercut banks, no two net pulls are ever the same. For Jackson and Martin, moments like these are what make fieldwork worth it.

madtom—exactly what they’re looking for. With over 20 species of fish swimming through the creek’s narrow channels and undercut banks, no two net pulls are ever the same. For Jackson and Martin, moments like these are what make fieldwork worth it.

As part of Sewanee’s Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) program, they’re spending the summer working alongside Visiting Assistant Professor of Biology Grady Wells to explore the ecosystems of nearby streams. Martin, a life science research fellow in the Biology Department, is working on two different projects. For the first, he is tracking the age class structure of the digger crayfish in the drift fence vernal pool, a rainfed body of water near campus, where they discovered a species of digger crayfish. It marked the first recorded presence of this species on the Domain and Cumberland Plateau. For the other, he is studying environmental preferences and aggregation behavior of the aforementioned slender madtom.

As part of Sewanee’s Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) program, they’re spending the summer working alongside Visiting Assistant Professor of Biology Grady Wells to explore the ecosystems of nearby streams. Martin, a life science research fellow in the Biology Department, is working on two different projects. For the first, he is tracking the age class structure of the digger crayfish in the drift fence vernal pool, a rainfed body of water near campus, where they discovered a species of digger crayfish. It marked the first recorded presence of this species on the Domain and Cumberland Plateau. For the other, he is studying environmental preferences and aggregation behavior of the aforementioned slender madtom.

Jackson’s research focuses on the length-weight relationships of creek chub. She collects them from three different stream sites near Sewanee, two located on the plateau and one at the base on the Highland Rim. “It's fun that we get work in streams right here on the Mountain. I get to interact with our campus in a different way,” she says.

Jackson, Martin, and Wells spend hours in the water together, and their fish-collecting methods capture the heart of fieldwork as something creative, hands-on, and grounded in the local landscape. They use a combination of techniques to collect the fish they’re studying, the most efficient being the backpack electrofisher, a portable device with two metal rods that temporarily stuns aquatic animals without harming them, causing fish to float to the surface.

Jackson, Martin, and Wells spend hours in the water together, and their fish-collecting methods capture the heart of fieldwork as something creative, hands-on, and grounded in the local landscape. They use a combination of techniques to collect the fish they’re studying, the most efficient being the backpack electrofisher, a portable device with two metal rods that temporarily stuns aquatic animals without harming them, causing fish to float to the surface.

The species of crayfish they’re studying, however, is a burrowing type, meaning even if shocked, they remain underground. To catch them effectively, the team uses baited minnow traps. The crayfish, Martin notes, are attracted to strong-smelling bait. “[They] love eating anything that smells bad basically, or smells strong,” he explains. “And I mean, what better food item than some slimy hot dogs?” This method has proven successful, with a single pull capturing 107 crayfish.

Other projects use different tools: The madtom study uses 8x4 feet tall nets, held upright on wooden poles, to create a barrier in the stream. While one person holds the net in place, another stirs up the gravel upstream, driving fish forward until they collect in the net.

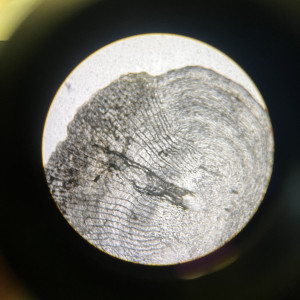

After the fish are collected, the team takes careful measurements to record their size, weight and age. “If you were to cut down a tree and look at the cookie [a cross-section slice of the tree], you can count the rings and tell how old the tree is based on growth layers. It’s the same thing with the fish scale,” says Jackson. “We put them under a microscope to magnify them and look for nodes where there’s a lot of growth at once—that signals one year.”

After the fish are collected, the team takes careful measurements to record their size, weight and age. “If you were to cut down a tree and look at the cookie [a cross-section slice of the tree], you can count the rings and tell how old the tree is based on growth layers. It’s the same thing with the fish scale,” says Jackson. “We put them under a microscope to magnify them and look for nodes where there’s a lot of growth at once—that signals one year.”

The data they gather may help future conservation efforts as human activity continues to alter Tennessee’s waterway. These smaller species play a crucial role in freshwater ecosystems, and with increasing disturbances, such as agriculture or mining, it is important to understand how these highly sensitive species respond to their rapidly changing environment. “Being able to find that line between enjoying nature and giving it meaning is really neat,” says Martin, sharing a reminder that even the smallest fish are a part of something much bigger.