"Sewanee started me on a grand adventure."

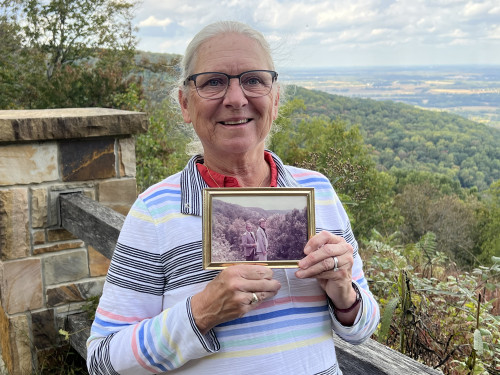

Sewanee’s official colors are purple and gold, but when Mary Cupp, C’78, recalls her time on campus, she mainly pictures green. Growing up in western Nebraska, Cupp says, she became accustomed to flat landscapes. In Sewanee, “the trees were so interesting. Sometimes it could feel like they were closing in on you.” When the Mountain’s foliage got overwhelming, Cupp says she’d visit Green’s View or the Sewanee Memorial Cross—places with open space. These spots were “kind of like home.”

Despite occasional moments of nostalgia as an undergraduate, Cupp says she’s glad she ventured across the country to pursue her education. “Sewanee started me on a grand adventure.” Recently, she marked her 43rd consecutive year as a University donor, and in 2021 she established the Mary Cupp Cornerstone Scholarship, which supports high-achieving students from all backgrounds and geographical locations. Cupp describes her philanthropy as an expression of gratitude for the doors Sewanee opened—and a means to ensure that deserving students can experience their own fulfilling journeys.

("I wanted to bring them back once more, since they cannot come in person," she says.)

Cupp’s post-Sewanee “adventure” has included stops in diverse parts of the globe. Prior to her recent retirement, she served for nearly 40 years as an attorney for U.S. Customs and Border Protection, rising to the senior executive level with administrative responsibility for offices in five Western states and the U.S. Pacific territories. She arrived at Sewanee thanks to a Wilkins Scholarship, which, at the time, covered full tuition for all four years. Cupp was also pointed toward the Mountain by her uncle, Mac Petty, who coached basketball and soccer at the University from 1973 to 1976. She notes that she was Sewanee’s only Nebraskan undergraduate during her college years, and she had no opportunity to tour the campus before matriculating. “The first time I saw Sewanee was when I was dropped off there—[similar to] how I imagine lots of young men experienced the University in the 19th century.”

Cupp majored in English but says she enjoyed exploring courses across a range of disciplines. “I took a lot of astronomy classes, for example, with [Emeritus Professor of Physics] Francis Hart.” Through an independent study led by Hart, Cupp researched astronomical observations in Chaucer-era England and compared them to actual astronomical events—a perfect blend of her academic interests. Another academic highlight, she says, was taking classes with beloved Professor of English Ted Stirling, C’62, who passed away in 1994. “He had this lovely, deep voice and would read regularly from the poems or plays we were talking about. He made them come alive.”

Though Cupp describes herself as “not particularly athletic,” she joined Sewanee’s fencing team to fulfill a physical education requirement. As the team’s only female member, she says she developed a distinctive competitive style, which she didn’t fully appreciate until she participated in Tennessee’s state fencing tournament. “It was the first time I’d fenced against another female, and one of the coaches told me, ‘You’re being a little aggressive. You need to back off a bit. You’ve only fenced with men, right?’”

Navigating gender imbalances wasn’t new to Cupp—and it has been a bit of a recurring theme, she notes. “Most of my life has been [spent] in predominantly male environments.” During her Sewanee years, she earned money over the summer by supervising roguing crews in western Nebraska’s cornfields. As Cupp explains, roguing involves removing undesirable parts of the corn crop. She managed all-male groups of juvenile offenders who had been court-ordered to the task. “It was hot, difficult work,” she says. As a young, female supervisor, “I had to develop a thick skin and be able to stand up for myself.”

After graduating, Cupp enrolled in Tulane University School of Law, earning a J.D. in 1981. “I had no plans to work for the federal government,” she says, but a yearlong federal clerkship led to a position with the U.S. Custom House in New Orleans. Cupp credits Sewanee for equipping her with the critical thinking skills and adaptability needed to excel in law school and to advance in her early career.

Ultimately, Cupp advised multiple presidential administrations during her nearly four-decade career, but she emphasizes that her position wasn’t political. “It sounds kind of corny, but we were told that we worked for the American people, not any one person.” As a civil servant, Cupp says, she was tasked with objectively determining the legality and feasibility of proposed border protection and customs policies, then relating her findings. Occasionally, “political appointees told me they were not going to take my advice on the best way to go,” she says. “And while I didn’t think it was the best choice, they had the authority to make the decision.”

Cupp also oversaw a number of money-laundering cases, which sometimes necessitated international travel. She notes that she was in Panama a year after the apprehension of former military dictator Manuel Noriega, and “the impact of capturing a foreign leader and bringing him to the United States was still very evident,” including “bullet-ridden walls” and other battle damage. This trip occurred during a period when government employees were at higher risk for kidnapping in South America, Cupp says, and the State Department provided briefings on what to do in case of abduction. “In Panama, the only way we traveled was in armored cars. They didn’t want us roaming around.”

Occupational risks aside, Cupp says she truly liked her work. “Most civil servants are very dedicated,” she says. “It’s a calling, not a job.” Cupp views New Orleans as the launching pad for her career and thanks Sewanee for paving the road to Louisiana. “If it hadn’t been for the University’s generosity and my scholarship, I don’t think I would have gotten to New Orleans,” she says, “because I wouldn’t have received the solid education that put me on that path.”

Associate Vice President for Advancement Terri Griggs Williams, C’81, says the profound effects of scholarship funding can’t be overstated. “It may sound clichéd, but scholarship support changes lives.” Williams commends Cupp as a “remarkable Sewanee alumna who has firsthand experience with the power of scholarships and has chosen to pay it forward.”

Cupp says she rarely makes it back to the Mountain, but she recently came across a special memento from her Sewanee days—a wooden quail she purchased from local folk artist Elvin King in 1978. She recalls visiting King with a group of Sewanee friends, after reading an article about his sculptures in The Sewanee Purple. Though he passed away in 2004, King still has a lively creative presence. (A YouTube video shows him peeling an apple with a chainsaw.) Cupp says her conversation with King was memorable, even surprising. “I talked to Mr. King for a while, and at one point he said, ‘I have to ask you—I see they talk like you on TV all the time. But does everybody talk like you where you live?’ And I thought he was the one with the accent!”