"There's a lot of talent out there, and a place like Sewanee is a great environment for development and for young people to gain exposure to a variety of disciplines."

As the founder of Treat Yourself to Health, a holistic medical practice in Atlanta, Georgia, Dr. Serena Satcher, C’85, provides personalized, integrative and functional medicine health care to people from all backgrounds. Though she says she knew from an early age that she wanted to pursue a career in medicine, she didn’t expect to gain firsthand hospital experience on the Mountain. While competing in intramural track as a Sewanee sophomore, Satcher broke her ankle—an injury that landed her at Emerald-Hodgson Hospital for a week. “I had terrible tennis shoes,” she says. “I was doing a long jump, and I landed in the pit. I heard three cracks.” Eric Benjamin, C’73, Sewanee’s former director of multicultural affairs, took Satcher to an orthopedic surgeon, who recommended an operation. Ultimately, Satcher persuaded the physician to go with a noninvasive option. “I’m sure he thought I was a piece of work, but I ended up in a full-length cast.”

These days, Satcher encourages her patients to trust their instincts and advocate for their well-being. She also honors the support she received from the Benjamin family and other Sewanee community members by contributing to areas of the Sewanee Fund that promote multiculturalism, such as the University’s Division of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. “I think it’s important to continue what Mr. Benjamin started and to enable opportunities for people who might not [otherwise] get the exposure,” she says.

For her part, Satcher says she was fortunate to encounter a broad range of ideas, people, and places before enrolling at Sewanee. Her father, Robert Satcher, held a number of high-level positions at historically black universities, including serving as academic dean of Voorhees College in Denmark, South Carolina, and president of St. Paul’s College in Lawrenceville, Virginia. Her uncle, David Satcher, served as the 16th surgeon general of the United States during the Clinton administration. Serena says her father’s career took their family around the world and brought renowned guests to their dinner table. “I remember meeting Jesse Jackson a couple of times,” she says. She also recalls attending church in Hampton, Virginia, with the female NASA mathematicians who inspired the movie Hidden Figures. “We just took them for regular, everyday people in our community.”

The Satchers’ social circle additionally included Sewanee historian Arthur Ben Chitty, C’35, H’88, P’68, P’77, and former History Professor and Dean of the College William Brown Patterson, C’52. When Serena was a senior in high school, the Chittys invited her and her younger brother, Bobby, to tour Sewanee’s campus. At the time, Bobby was strongly considering attending MIT, where he eventually enrolled. “I loved the scenery of the Mountain,” Serena says. “Believe it or not, it came down to Sewanee versus MIT.” She credits her mother with pointing her toward Sewanee. “I think my mother had some concept of what I needed for my well-being.” Satcher adds that Sewanee’s small class sizes were, and are, a selling point. “My professors—the ones who are still alive—remember me.”

Having lived in a variety of places throughout her childhood, Satcher says it wasn’t difficult to adjust to small-town University life, though “at that time, there were only five Black students at [Sewanee].” She developed a connection with her academic advisor, Professor of Biology Henrietta Croom, P’87, which lasted well beyond graduation—Satcher notes she and Croom last spoke about a year before Croom’s passing in February 2024. She also gained close friendships working as a student athletic trainer assistant. “Working with all the athletes was a privilege. We were the hands-on folks—icing their injuries, putting them in the sauna, wrapping their ankles and wrists before games. I love sports anyway, so it was great.” In particular, Satcher says, she enjoyed getting to know Reggie Benson, C’87, and Kevin Jones, C’87, two Black students on the football team. “My dad is from west Anniston, Alabama, and Kevin grew up in west Anniston,” she says. “I didn’t find out all the details until after Sewanee, but my mom’s younger sisters used to babysit Kevin and his sister.” Satcher says she still chats with Jones regularly.

After earning a B.S. in biology, Satcher moved to Nashville to attend Meharry Medical College, a historically Black medical school. Though she excelled in her coursework, she says she also made time for fun. “Meharry had a party scene, just like Sewanee has a party scene.” After a long week of studying, she and her classmates would go to Shoney’s for a snack before heading to a party. All in all, Satcher says she had no problem staying focused—maybe partly because her uncle, David Satcher, was president of Meharry during her years there. “Meharry is small enough to where he saw me all the time.”

the Dunwoody Community Garden

The close-knit communities that Satcher found at Meharry and Sewanee were a contrast with her residency at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. “I was the only Black person in my residency the entire time I was there,” she says. Luckily, she notes, her time as a resident coincided with her brother, Bobby’s, years as a medical student in the Harvard-MIT Program in Health Sciences and Technology. “We would get together and have coffee, usually one day a week, on Harvard’s campus.” Bobby continued on an impressive career trajectory: he served as a NASA astronaut and is currently an orthopedic surgeon and medical researcher.

Satcher worked in a wide array of settings before starting her practice in Atlanta. For four and a half especially challenging years, from 2017 to 2021, she served in the Department of Veterans Affairs as a functional medicine and physical medicine and rehabilitation physician with the War Related Illness and Injury Study Center (WRIISC). “That ended up being a very special experience because I got a lot of exposure to learning about PTSD.” Satcher says the WRIISC supports veterans from 22 states, and many of the patients she treated had complex PTSD symptoms, related not only to their military service but also to childhood experiences and military training.

As she focused on helping veterans to regain their lives and function, Satcher says she also tried to “change the language” used to describe PTSD behavior. Specifically, she urged her WRIISC colleagues to reconsider describing veterans as “noncompliant” and to instead frame behavior in terms of abilities. “I didn’t want to call it ‘noncompliance’ if we were expecting [patients] to do more than they were capable of doing at that point in time,” she says. Replacing negative terminology with positive, achievement-oriented language was empowering veterans to “have a win.”

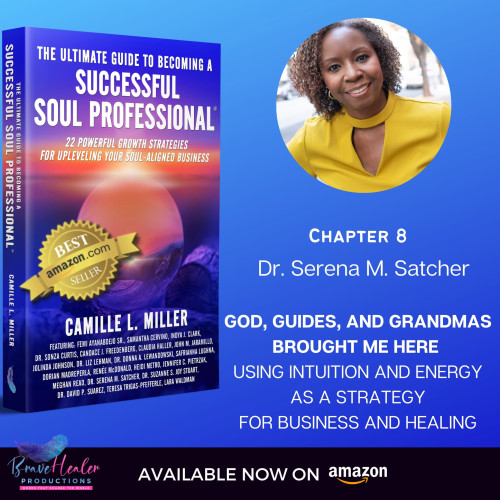

By the fall of 2021, Satcher restarted her solo practice in Atlanta. Earlier in her career, she had attended a weeklong workshop at Canyon Ranch, a wellness center specializing in holistic treatments. “That’s what really got me into functional and integrative medicine,” she says. “Once you learn that lifestyles and stress cause illnesses, you want to help people reverse what’s happening and avoid medicine or surgery—or an emergency or trauma.” Satcher says the techniques she learned at Canyon Ranch were effective in shrinking uterine fibroids that had caused her significant discomfort for many years. As part of her work at Treat Yourself to Health, she now creates online learning modules centered on healing strategies that address factors such as nutrition, sleep, stress level, exercise, and environment. She also gives in-person and virtual presentations, hosts a podcast, and writes a blog. The goal is simple, as described on her practice’s website: to “help people figure out what’s wrong, whatever it is.”

Though Satcher hasn’t visited Sewanee recently, she served as a University trustee in the early 2000s and has participated in Beyond the Gates and Benjamin Network events. She says she’s eager to return to the Mountain during Dr. Renia Rush Dotson’s, C’88, tenure as chair of the Board of Regents—she and Dotson have remained good friends since their overlapping time as undergraduates. While acknowledging that her upbringing primed her to thrive on any college campus, Satcher says she hopes her Sewanee Fund contributions will help students discover their potential on the Domain. “There’s a lot of talent out there, and a place like Sewanee is a great environment for development and for young people to gain exposure to a variety of disciplines.”

Whitney Franklin, executive director of the Sewanee Fund and advancement services, agrees with Satcher’s assessment. “I’ve been working with the Sewanee Fund for more than a decade, so the students I met during my early years on campus are now well into their career journeys. It’s rewarding to see how much our Sewanee graduates achieve and to know that the Sewanee Fund facilitates those accomplishments. Our donors are definitely part of something big—and we’re grateful.”