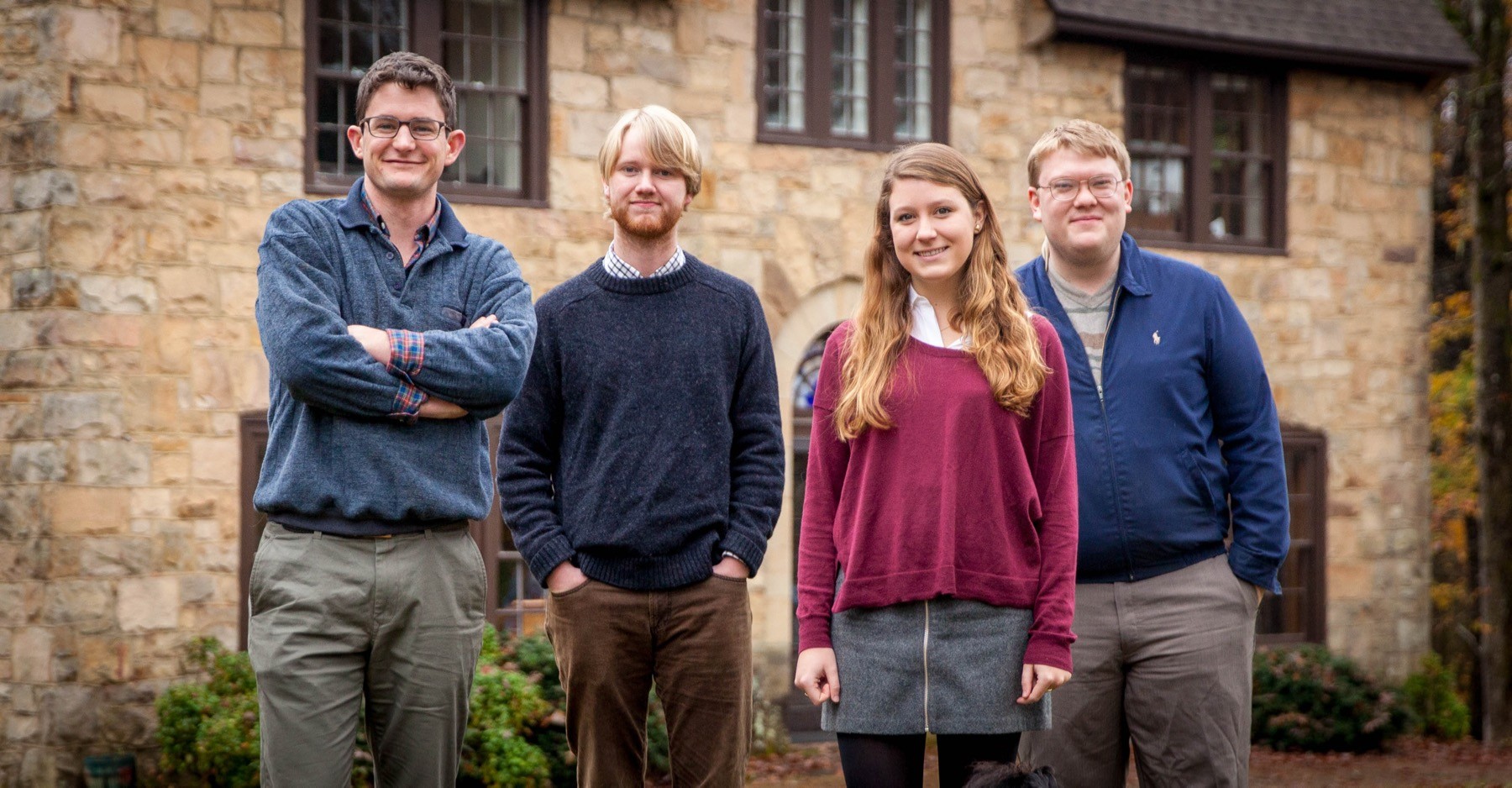

Left to right: Managing Editor Alec Hill, C'16, with Editorial Assistants Walt Evans, Annie Adams, and Spencer Hupp, all C'17.

Youth Brigade

Editor Adam Ross staffs the venerable Sewanee Review from a single source—recent Sewanee graduating classes.

BY HENRY HAMMAN

A lec Hill, C’16, the managing editor of the Sewanee Review, is leaning back in his desk chair, wrapping up an interview about his job at the venerable literary magazine. Over the last hour, he’s talked about how he ended up here, what it’s like to work closely with the Review’s world-class contributors, and the fragile nature of literary judgment. But there’s one last question to answer: Does he like the work?

“On the deadliest day, I get to spend a few hours reading,” he says. “It’s pretty ludicrous to me that I get paid to do that.”

Hill is surely one of the youngest senior editors of a major literary magazine in the United States today. His portfolio of responsibilities includes everything from reviewing submissions from hopeful authors to managing the subscription list to working with Editor Adam Ross on developing new marketing strategies, including social media, for the Review.

He says Ross told him his job was “making the trains run on time.”

He is 23 years old, a Class of 2016 Sewanee English major. And besides Ross, he is the oldest member of the Review's full-time editorial staff. He started work at the Review in 2016, shortly after Ross became editor.

Hill and the rest of the editorial team are ensconced in an elegant stone house on South Carolina Avenue, the former residence of longtime University administrator Tom Watson and his wife, Gail.

Stripped of its furnishings and sparsely fitted out with office desks and computer monitors, the Review’s new digs lack the clutter one usually associates with the lairs of writers and editors—disorderly piles of paper, groaning bookcases, and photos and prints hung seemingly at random. But give the new folks a bit of time—after all, the rest of the staff started work just over four months ago, about the time the Advent Semester started.

Annie Adams, Spencer Hupp, and Walt Evans, the balance of the full-time editorial staff, share the same title: editorial assistant. They also share the same undergraduate major, English, the same graduating class year, 2017, and the same alma mater—Sewanee.

Hiring from Sewanee was part of Ross’s proposal when he was interviewing for the post as editor. He argued that the Review could be a training ground for aspirants to the writing life, a place where “smart, young, energetic people with comparatively little experience could step up” and start the journey to becoming literary talents.

For a number of years, the Review had offered one graduating senior a one-year internship at the magazine, billed as an opportunity to gain experience in the publishing industry. The stereotypical publishing intern spends the working day making coffee, fetching coffee, and, with any luck, having an hour or two to do the initial winnowing through what’s known as the “slush pile,” the unsolicited manuscripts that constantly arrive at publishers’ offices. And mostly, these jobs are unpaid.

The Review, however, is trying something different.

The three assistants are in charge of the slush pile. They read constantly—each one of them goes through perhaps 60 manuscripts a week.

Hill acts as a sort of traffic cop, assigning each unsolicited manuscript to two assistants. If these reviews are favorable, they pass the manuscript on to the third reader. If all three agree, the piece goes to Hill, and, if he agrees, that unsolicited manuscript ends up on the desk of the editor of the longest continuously published literary magazine in the United States.

Ross calls the team “the first line of defense of my time.”

But Adams, Evans, and Hupp don’t just winnow the pile; they are working with Ross, learning by doing, to bring out the best in a manuscript and to navigate the delicate relationship between writer and editor.

As the months go by, the apprentice editors say they are learning how to trust their literary sensibilities.

Adams says when she started at the Review, she found herself asking, “Who am I to say if a piece is good or not?” But she has to decide—it’s her job.

Hupp says the continual reading of submissions is helping him develop judgement. “If you read enough of what’s being written, you get a sense …”

But he’s also aware that making choices about the work he reads has real-life implications for writers. “In some respects, I’m destroying dreams when I hit ‘no.’”

All three editorial assistants share another element in their background—they all earned a certificate in Creative Writing from Sewanee, a program that is not quite a minor but requires four courses and a capstone writing project such as a collection of poetry or short stories, a novella, or a one-act play. Many of the courses are taught as workshops, with students critiquing the work of their classmates.

Ross alludes to the experience the trio brought with them to the job. “They came through the pipeline. These kids were so well trained.”

Now, however, they are no longer students, and instead of a professor, they have a boss; instead of living in student housing, they are living on their own, paying rent and student loans. They have embarked on careers in the writing life while they’re still in Sewanee.

Hill says the switch from being a student to an editor was “profoundly disorienting.” Instead of having teachers to guide his taste, he’s had to develop “a strong sense of what’s good. It’s the dead opposite of what they teach you.”

“It’s weird,” says Evans. “I’m only 22. I have a lot of friends who are still in college. But this is an actual job; we work 40 hours a week.”

Hupp says he sees the job as the real “capstone of my Sewanee education. There aren’t any other jobs like these.”

How long will these new editors stick around? None of them know for sure, though they know their time at the Review is just the starting point.

They are considering graduate study in creative writing, doing their own writing. Right now, though, they’re soaking up the experience, amazed at their good fortune. Adams speaks for them all when she says, “I’m really lucky to be here.”