a homegrown pavilion for lost cove

This summer, a new pavilion will be built in Lost Cove using wood from pine trees that Sewanee forestry students helped plant more than 50 years ago. Current students were involved in every step of the harvesting process, from measuring and selecting trees to milling the lumber. Here’s what it looked like.

In February, Forestry Professor Scott Torreano took his silviculture students to a stand of loblolly pines to take measurements and mark the trees that would later be harvested. The trees were planted by former Sewanee forestry students and members of the Forestry Department field crew sometime between 1957 and 1962 on land that had previously been damaged by poor logging practices.

Loblolly, which is not native to the Domain, was planted here for teaching and research purposes. “They were trying to demonstrate that landowners in this part of the South had an opportunity to plant pine and to manage pine on their lands for this new thing called the pulp and paper industry, which was evolving at that time,” says Torreano.

Torreano shows students how to read a forester’s “scale stick.” Students will stand 66 feet from a tree—a distance known as a “surveyor’s chain” or a “logger’s chain”—and use the scale stick to estimate the tree’s height. After measuring the tree’s height and diameter, the tool is used like a slide rule to predict the amount of usable wood in the tree.

After estimating the usable wood in a tree, Leslie Vargas, C'21, marks it for harvesting. Her classmates would later stop by to jury her work, asking about her rationale for marking this particular tree and what its removal might mean for the trees around it.

In addition to choosing trees for harvest, students identified some of the best trees in the stand to leave in place for aesthetic as well as teaching and research purposes.

In March, it was time to harvest the trees the silviculture students had identified and marked. Under the watchful eye of Domain Ranger Sandy Gilliam, Thomas Simerville, C’20, makes an opening notch cut, which will constrain the direction of the tree’s fall. The placement of the cut is determined by the sawyer after considering a number of factors including optimal fall placement, the tree’s size, and any lean it may exhibit.

With the opening cut made, Simerville moves to the opposite side of the tree to make the felling cut, releasing the weight of the tree to fall in the direction of the notch. Student sawyers have had extensive training in a class in chainsaw safety and directional tree felling endorsed by the U.S. Forest Service.

Timberrr! The big tree threads the needle to fall right where Simerville and Gilliam want it. “If you hang a tree like this in any other trees, it’s a real problem because that tree is under stress and you have to cut it to release it,” says Torreano. “It’s a mess when that happens.”

After trees are felled, they’re “bucked,” cut into specific lengths— eight feet, 10 feet, 12 feet—so that the resulting lumber will match the needs of the building specified by the architect.

Sandy Gilliam and Gillan Junglas, C’20, attach a choke chain to a bucked log so that it can be hauled out of the woods.

Sandy Gilliam moves logs to prepare for milling. Torreano points out that the grapple loader used here is a smaller machine than would normally used by loggers. “It was perfect from a sustainability standpoint. There was so little damage done to the remaining trees and to the soil, to the forest floor, by using this machine. It was the perfect match for what was being done.”

In April, miller Bill Sandusky from Maryville, Tennessee, was hired by the University to bring his portable sawmill to Sewanee to turn cut trees into usable lumber.

Sandusky cuts a square “cant” out of the center of a log to saw into boards. “You can see the entire life of that tree by looking at its rings,” says Torreano. “There’s the early life of the tree in the center, and then you see the 1960 ice storm and the tree responds really well. Eventually, growth slows down as conditions in the forest start to become really competitive for light.”

After being cut, boards are sorted by length and “stickered”—placed on small pieces of wood that separate the boards to allow air circulation so the wood doesn’t degrade or get moldy.

“Students love to get out and work with their hands,” says Torreano. “It makes it contextual for them. There’s nothing like showing students trees and saying, ‘The silviculture class 60 years ago planted these trees.’ That makes the sustainability connection more real to them. They know that a Sewanee student in the same class that they’re taking, 20 or 30 or in this case 55-plus years ago, planted those trees and wondered ‘What will these trees look like in the future?’ Now these students are part of the answer to that question.”

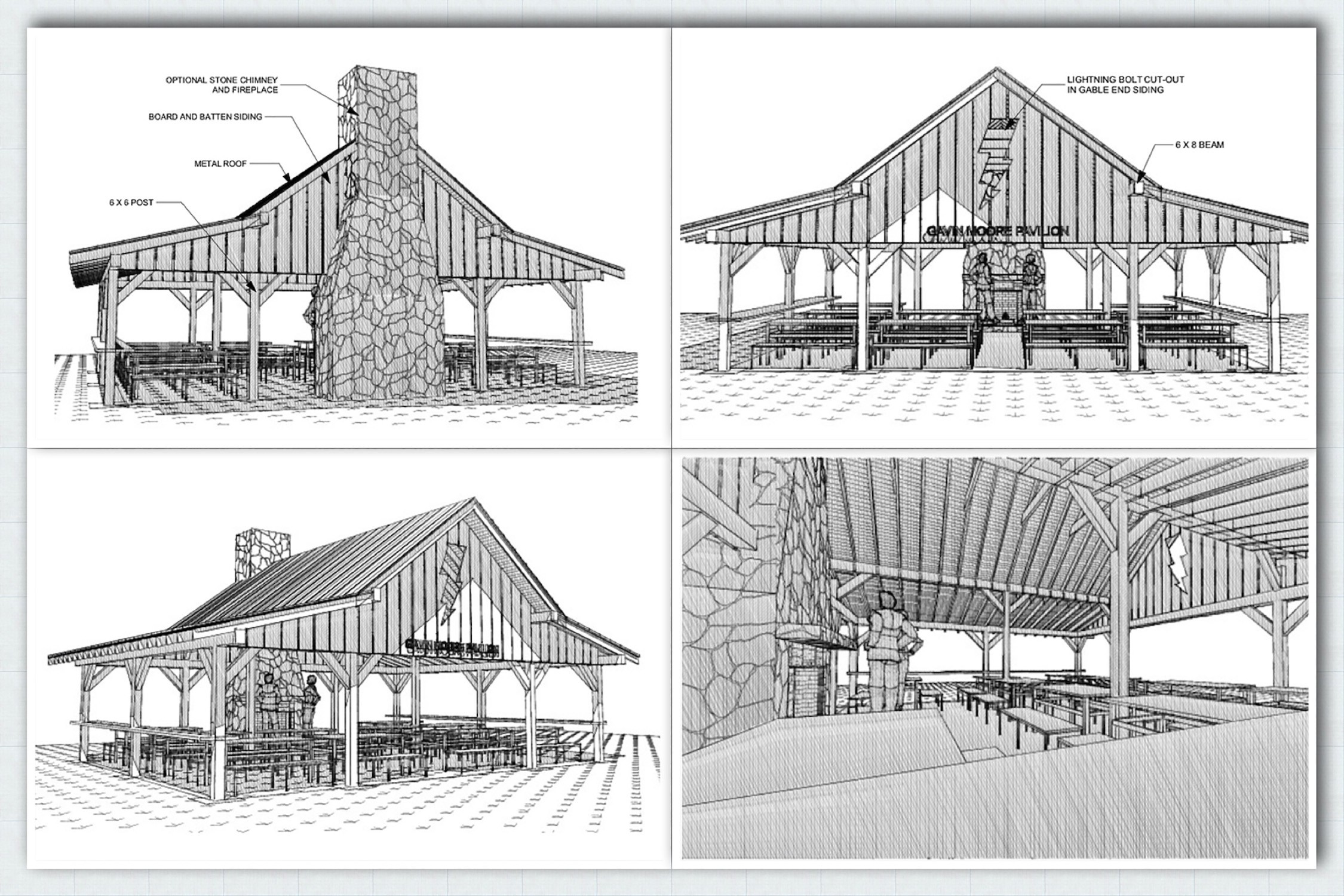

The Gavin Moore Pavilion, designed by architect Patton Watkins and funded by alumni friends of Gavin Moore, C’93, will take shape at the bottom of Lost Cove this summer, providing a welcome shelter and outdoor classroom for visitors and Sewanee classes. The fact that it will be built with trees both planted and cut by Sewanee students is important to Torreano. “It’s the whole idea of sustainability,” he says. “We train students to interpret natural landscapes. As part of that, we use natural resources, and that gives students an idea of sustainability and scale that’s really important.”