Bringing The Family Fang to Film

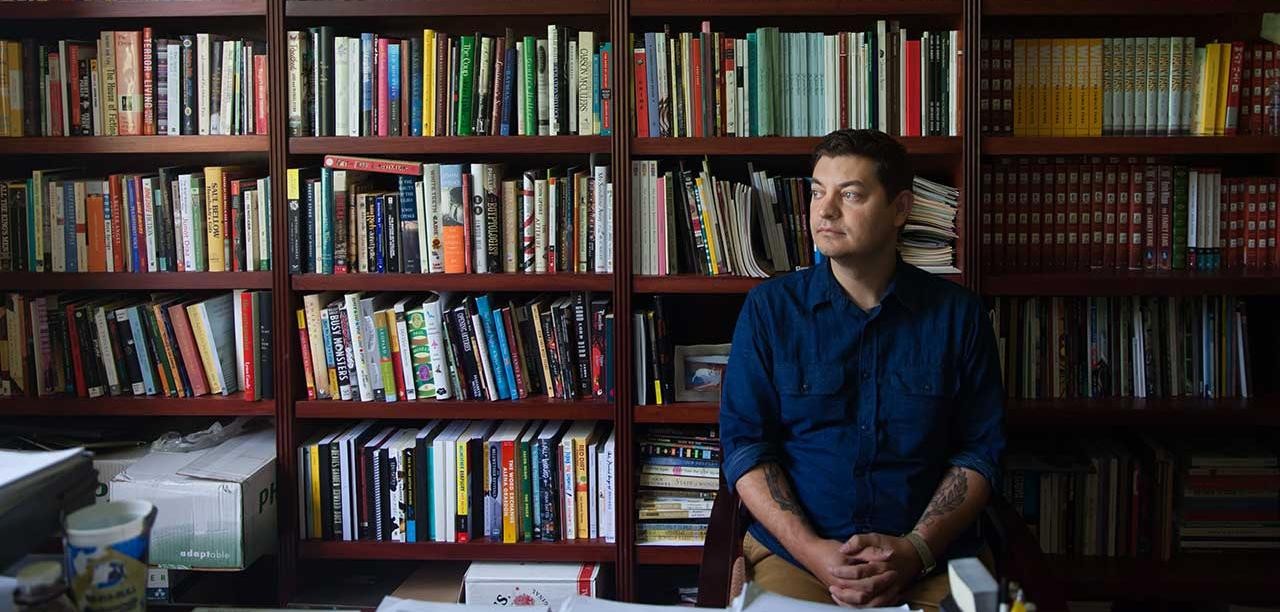

How Kevin Wilson's debut novel made it from Sewanee to Hollywood.

W hen Kevin Wilson takes a seat in a movie theater in Toronto next week to watch the world premiere of the film adaptation of his critically acclaimed bestselling novel The Family Fang, he will be like most of the other guests there—he’ll be seeing the movie for the first time. Five years after Wilson finished writing his novel, the quirky family drama is hitting the big screen at the Toronto International Film Festival on Sept. 14 and Wilson will be there, popcorn in hand.

The Family Fang tells the story of Annie and Buster, the children of performance artists Caleb and Camille Fang, who have subjected their progeny to an unconventional childhood by continually having them play roles in their parents’ unsettling public performance pieces. After suffering a series of professional and personal disasters, the adult Fang children return home to reckon with their past and the older Fangs, who have always been more committed to their art than their parenting.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the story of how the film came to be reads like a screenplay: An assistant professor of English and coordinator of the creative writing program at a small liberal arts college in Tennessee (Wilson) publishes a debut novel. An A-list Hollywood star who happens to live in Tennessee (Nicole Kidman) reads the book and options the movie rights. A beloved TV and film actor (Jason Bateman) decides he wants to make the movie as his second directorial effort. The stars take the lead roles in the film, sign up more outstanding talent (including Christopher Walken), and ask a Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright (David Lindsay-Abaire) to write the script.

It all started with a cup of coffee. After receiving word of Kidman’s interest in The Family Fang, Wilson met the Nashville-based actress at a coffee shop there and was immediately struck not only by her superstar presence, but by her intelligence and determination to get the film made. “She had read the book really closely and she had these ideas of what the book was doing thematically that I found really interesting,” Wilson says. “What she really cared about was picking apart the work and figuring out how she could do something with it. The minute I met her, I thought, ‘Oh, she knows what she’s doing. If it’s going to get made, she’ll get it made.’”

Kidman and Per Saari, her partner in the production company Blossom Films, asked Wilson if he would adapt the novel for the screen, but he declined. Wilson had never written a screenplay and, he says, “I didn’t want to be the reason the movie didn’t work out.” So Kidman and Saari enlisted the help of David Lindsay-Abaire, who had adapted the screenplay for Blossom’s first movie, Rabbit Hole, from his play of the same name, which won the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for drama.

Wilson says that Lindsay-Abaire’s screenplay diverges from the novel in some significant ways but that the changes help make the story work for film. In the movie, the Fang children are older than they are in the book, in part to accommodate Kidman and Bateman in the roles. The setting was moved from Tennessee to upstate New York, to give the Fang parents access to the New York art world and, more practically, because the state of New York offered the producers better tax breaks than Tennessee did. And the Fang son is no longer named Buster because Bateman didn’t want viewers to associate the character with a brother of the character Bateman played in the TV series Arrested Development, who was also named Buster.

“[Lindsay-Abaire] really streamlined things,” Wilson says. “He blended characters, he changed plot points in really elegant ways so when I read the screenplay I thought, ‘They’re doing something really interesting here.’ It’s different from the book, but it’s a really incredible script.”

As a viewer, Wilson is interested to see how the story plays on the big screen. “What movies have over books is the specificity of detail,” he says. “With fiction, you can write eight pages on what a character looks like, and as hard as you try, you’re still dependent in some ways on the imagination of the reader. With film, the characters look exactly the way you want them to look, so you get the wonderful level of detail that makes film so interesting.”

Some of that detail was on display when Wilson and his wife, poet and Sewanee Review Managing Editor Leigh Anne Couch, visited the set during filming in Nyack, N.Y., last summer. The producers rented an old house to film in, removed every bit of the owners’ belongings, and created the Fang house with meticulous care. They hung old wallpaper, brought in ’70s-era furniture, and filled the rooms with Fang-appropriate provisions, down to the tiniest details, including the magazines on the coffee table, whether they would actually appear in the film or not. “They kept asking ‘Is it how you imagined it from the book?’” Wilson says. “And I was like ‘No, it’s so much better.’ I didn’t have that level of imagination when I was thinking about the house.”

That day on set in Nyack, Wilson got a taste of what it might be like to see the Fangs come to life. “I was watching them film and hearing lines that I wrote five years ago being spoken out loud by these characters,” he says. “It was really bizarre.”